After a Century of Progress, Our Lifespans Are Hitting a Wall

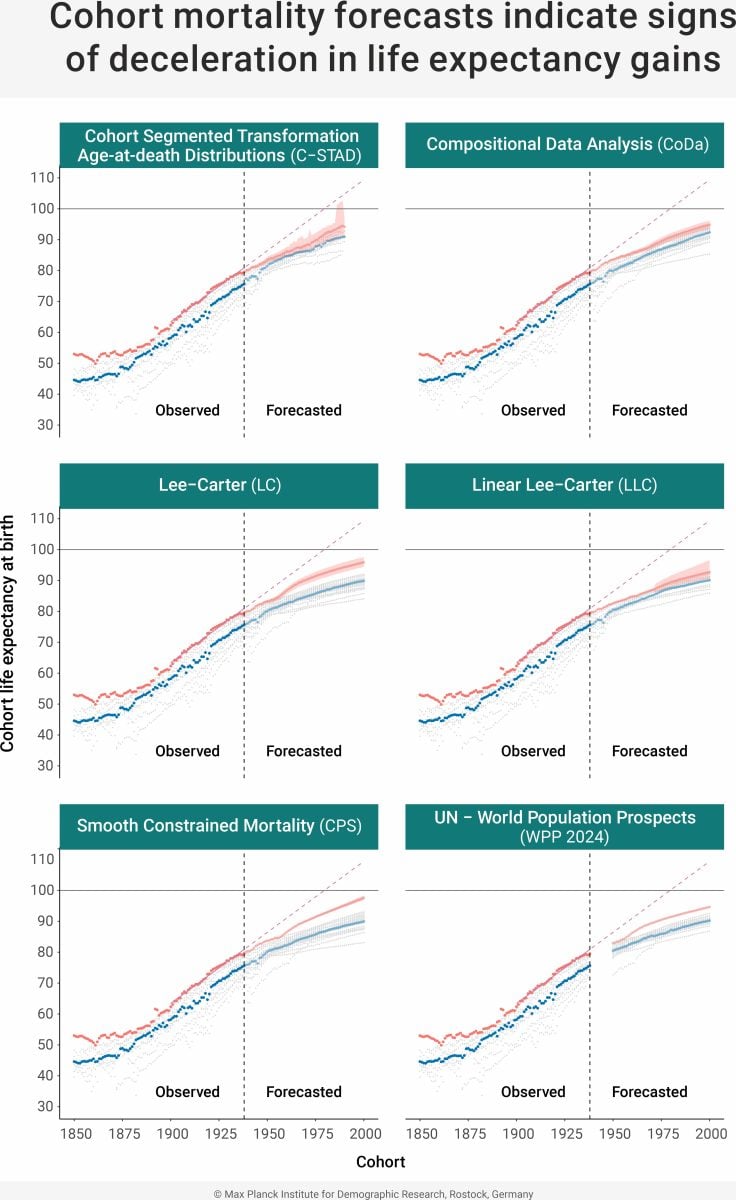

Researchers used six different methods for their calculations and arrived at the same conclusion.

The future trajectory of life expectancy remains a subject of considerable debate among scientists. At the start of the 20th century, life expectancy increased at a remarkable pace: individuals born in 1900 lived an average of 62 years, while those born in 1938 reached about 80.

In a study recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), José Andrade (Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR)), Carlo Giovanni Camarda (Institut national d’études démographiques (INED)), and Héctor Pifarré i Arolas (University of Wisconsin-Madison) examined whether people born between 1939 and 2000 would experience comparable gains in life expectancy. Their analysis focused on 23 high-income countries with low mortality rates.

“If today’s generations were to follow the same trend as the one observed during the first half of the 20th century, someone born in 1980, for example, could expect to live to 100,” explains José Andrade, lead author of the study and a researcher at MPIDR. “We investigated whether the pace of life expectancy gains is slowing down for current alive cohorts.” To explore this, the researchers projected the life expectancy of these groups using data from the Human Mortality Database (HMD). They applied six distinct mortality forecasting methods—statistical tools that use historical and current mortality patterns to predict future lifespans—to estimate how life expectancy may evolve.

“To ensure robust results, we did not just use one method, but several: some well-established ones, including the United Nations World Population Prospects, and others representing the cutting edge of mortality forecasting,” said Andrade.

The researchers applied two main strategies to develop the cohort mortality profiles:

- Period-based methods included approaches such as Lee-Carter, Smooth Constrained Mortality, Compositional Data Analysis, and the United Nations World Population Prospects (2024).

- Cohort-based methods included the Linear Lee-Carter model and the Cohort Segmented Transformation of Age-at-death Distributions.

Little room for improvement

“All forecasting methods show that life expectancy for those born between 1939 and 2000 is rising more slowly than in the past. Depending on the method used, the rate is slowing by between 37 and 52 percent,” explains the researcher. “We forecast that those born in 1980 will not live to be 100 on average, and none of the cohorts in our study will reach this milestone. This decline is largely due to the fact that past surges in longevity were driven by remarkable improvements in survival at very young ages.”

During the early 20th century, infant mortality decreased sharply because of advances in medicine and improvements in living conditions, which fueled the dramatic rise in life expectancy. Today, however, mortality in these young age groups is already so low that further gains are minimal. The team’s projections suggest that reductions in mortality among older populations will not progress quickly enough to offset the slower pace of improvement.

From 1900 to 1938, life expectancy rose by about five and a half months with each new generation. For those born between 1939 and 2000, the increase slowed to roughly two and a half to three and a half months per generation, depending on the forecasting method.

Andrade, Camarda, and Pifarré i Arolas regard this result as highly robust. They argue that even if the survival among adults and older individuals were to improve at twice the rate predicted in the forecasts, the resulting gains in life expectancy would still fall short of those achieved in the first half of the 20th century.

Forecasts are predictions, not certainties

Mortality forecasts can never be certain as the future may unfold in unexpected ways. Events such as pandemics, new medical treatments, or societal changes can significantly affect actual life expectancy. Consequently, life expectancy may not align with anticipated trends. Therefore, forecasts should always be considered as educated estimates. It is important to note that these forecasts apply to populations, not individuals.

Why is life expectancy research so important?

Changes in life expectancy affect social cohesion and personal life planning. Governments must adapt healthcare systems, pension planning, and social policies. At the same time, life expectancy influences personal decisions about saving, retirement, and long-term planning. If life expectancy increases more slowly, both governments and individuals may need to recalibrate their expectations for the future.

Reference: “Cohort mortality forecasts indicate signs of deceleration in life expectancy gains” by José Andrade, Carlo Giovanni Camarda and Héctor Pifarré i Arolas, 25 August 2025, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2519179122

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Source link